risk

Storm Surge: Planning for the Risk

Mobile home park on the north side of U.S. Highway 98 in Mexico Beach, Florida, washed away by the storm surge and wave impacts of Hurricane Michael. Nov. 2, 2018 (NOAA)

Mobile home park on the north side of U.S. Highway 98 in Mexico Beach, Florida, washed away by the storm surge and wave impacts of Hurricane Michael. Nov. 2, 2018 (NOAA)

If you were asked to define the word “risk”, what would your response be? What are the first things that come to mind? What questions are you asking? What are some things you would consider to be risky? Risk can take many forms, be it financial, personal injury, or even simple decisions that we all have to make on a daily basis. Consider two simple questions:

- Should I change the tires on my car?

- Should I change the tires on my car today

From a risk perspective, how has the question changed? The answer to the first question is a simple one because it’s general in nature. Yes, the tires should be changed somewhat routinely over the lifetime that you own or lease the car. Question two requires more thought, however, because it narrows the task down to a specific time frame. If your tires were changed recently and are in good shape, then it’s most likely business as usual. If you’re overdue, what are the potential consequences of not having your tires changed? Are you risking personal injury to yourself, your family, or others by not changing them? The risk profile changes based on myriad variables that exist. As this example conveys, the idea of risk is relatively simple in itself but can become complex quickly. Let’s define risk for now as the potential of gaining or losing something of value. That is to say:

Risk = Probability x Consequence

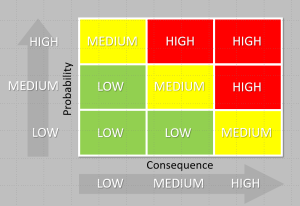

Yes, we threw some math at you, but this concept is relatively easy to grasp. Using the previous example, the overall risk profile is determined by multiplying the probability of a given event by the resulting consequence if that event occurs. So if there is a high chance of an event occurring, or the consequence is severe, then the risk to you would be high. One way to look at risk is by using a risk matrix, as shown below in Figure 1. Your risk increases if the probability of the event goes up or if the consequence of the event goes up.

Figure 1. Risk matrix showing different levels of risk based on the probability of an event and the consequence if that event occurs.

The event in our car example is blowing a tire on the interstate, and a potential consequence would be having a fatal accident due to the blown tire. That consequence is so severe that your risk is quite high. But let’s take the example a little further. Risk is further compounded by vulnerability. Let’s consider a new equation:

Risk = Probability x Consequence x Vulnerability

Using the same example, what are variables that could increase the vulnerability, and thus the risk of a fatal accident, in this scenario? Are there kids in the car? What speed is the car travelling? If the tire pops while backing out of the driveway, isn’t that much different than the tire popping while travelling 70 mph down a busy interstate? This is just one of many examples that we all encounter on a daily basis. If there is a consequence to an action you might take, then you are making a risk-based decision.

Risk Perception and Risk Tolerance

There are two other topics related to risk that we should touch on: risk perception and risk tolerance. First, risk perception is the subjective judgement people make about the severity and probability of a risk. Why is this important? Well, there are two main reasons:

- Actual risk usually doesn’t equal perceived risk

- Perceived risk varies from person to person

Why does this complicate matters? When people have to make decisions, it’s important that how they perceive the risk be equal to the actual risk of the event, or at least as close to equal as possible. This is especially true when there is a desired response or action that needs to be taken to protect life and property, as is often the case with weather. We can use a simple example to further understand this. If a tornado is on the ground moving towards a community, the desired action for people living within that community is to seek shelter. In this scenario, the cost of persons within that community not seeking shelter is very high given that their lives are potentially in peril. If people dismiss what that tornado could do to their community (e.g., “tornadoes always pass our city to the south”), then that can be a recipe for disaster, especially when the cost is human lives.

This leads us nicely into risk tolerance. How an individual responds to risk is governed by their risk tolerance, which is unique to both the situation and the person. Risk tolerance is the amount of risk that an individual is willing to accept with respect to a given event occurring. Turning back to the tornado example, let’s consider two hypothetical people that live in the community threatened by the approaching tornado; we’ll name them Sara and Monika. For the sake of example, let’s assume that Sara has a family with two young children and lives in a mobile home. Monika, on the other hand, lives by herself in a well-built house. If Sara and Monika have the same perception of the imposing risk, do these life factors change their respective risk tolerances? In the real world it’s difficult to say, but in this idealized example, let’s assume that it does. Monika does not have anyone in her care and also lives in a home that could withstand stronger winds than Sara’s mobile home. Is Monika’s tolerance for risk higher than Sara’s? It certainly could be, couldn’t it? Again, we understand that assumptions are being made here, but this is simply a hypothetical scenario to demonstrate how risk tolerances may change across individuals and circumstances unique to those individuals. All of this is to say that humans are complicated and risk perceptions and tolerances vary across all of us.

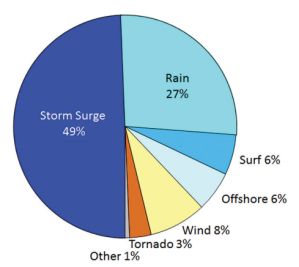

Circling back to the initial equation that we used to define risk, let’s establish a baseline for what the potential consequences are with respect to storm surge by looking at history. Storm surge is the abnormal rise of the ocean produced by a hurricane or tropical storm, and normally dry land near the coast can be flooded by the surge. Historically, about 50% of lives lost in landfalling tropical cyclones in the United States have been due to storm surge (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Causes of death in the United States directly attributable to Atlantic tropical cyclones, 1963-2012 (Rappaport 2014).

The mission statement of the National Weather Service charges us to “provide weather, water, and climate data, forecasts and warnings for the protection of life and property and enhancement of the national economy.” There is no clearer way to illustrate what the consequences are in this equation: the loss of human lives. Because the cost here is so high – arguably the highest – our risk tolerance for your safety is extremely low. We have absolutely no appetite for someone losing their life from a weather event. This idea directly informs many of the products that we use to communicate risk prior to and during landfalling storms, and we therefore use near-worst-case scenarios to encapsulate the full envelope of storm surge risk to communities. One life lost during a storm is one life too many. The remainder of this blog post will discuss two such products used by the National Hurricane Center and emergency managers to understand storm surge risk.

MOMs and MEOWs

Can we all agree that “MOMs” are extremely important? Well, yes, those moms are important in our lives, but that holds true for storm surge MOMs as well. Have you ever wondered how officials decide what areas should evacuate ahead of a hurricane? Look no further. MOMs (Maximum of the Maximums) are the rock from which the nation’s storm surge evacuation zones are built upon. MOMs are generated ahead of time. That is to say that these are precomputed maps meant for planning and mitigation purposes well ahead of a landfalling hurricane. In fact, one can view these any time as they are hosted on the National Hurricane Center’s website at https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/nationalsurge/. MOMs are generated by hurricane category (think 1-5) and depict the maximum storm surge height possible across all storm surge attributes. Attributes include things such as forward speed, storm trajectory, and landfall location, just to name a few. Because this product is designed for planning, you can think of the MOM as a worst-case scenario for a given category of a storm. MOMs do have limitations, however. Remember at the beginning of this post we asked the question “should I change the tires on my car?” MOMs are similar to that question because they are general in nature in that they lump all types of hurricanes into a single category. They can tell you what type of storm surge risk you would have from a category 3 hurricane, for example, but they’re not quite as helpful if you know that the category 3 hurricane will be moving toward the west (and not north or northeast for instance).

For this reason, the MOMs have a slightly more refined counterpart – MEOWs (Maximum Envelope of Water). MEOWs are like the second question we asked: “should I change the tires on my car today.” Since we said “today,” we know a little bit more about the actual situation we’re dealing with to make a better-informed decision. Similarly, once a storm or hurricane forms and is within 3–4 days of impacting the coast, we have at least some idea of how strong it could get, how fast it’ll be moving, and in what general direction it’s headed. We are able as forecasters to whittle down the worst-case MOM such that we only consider storms moving toward a particular direction at a particular forward speed — not all directions and forward speeds. Similar to the Maximum of Maximums, a MEOW is a worst-case for storms of a certain strength (for example, Category 3 hurricanes), but it’s more representative of what the storm surge at individual locations could be based on the attributes and forecasts of the active tropical cyclone. At 3 days out, there is still considerable forecast uncertainty, so the MEOW is meant to supplement the MOM, not replace it. As some might say, you can’t go wrong if you always trust your mom. The same adage goes for a hurricane storm surge MOM.

Hurricane Florence

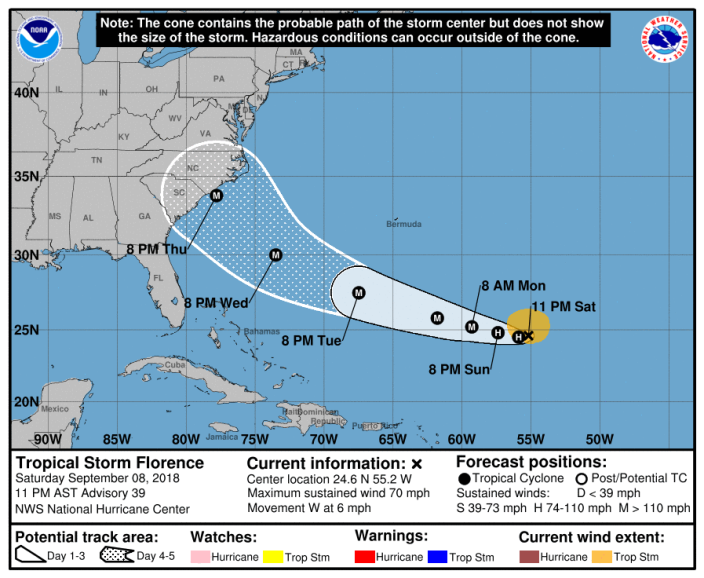

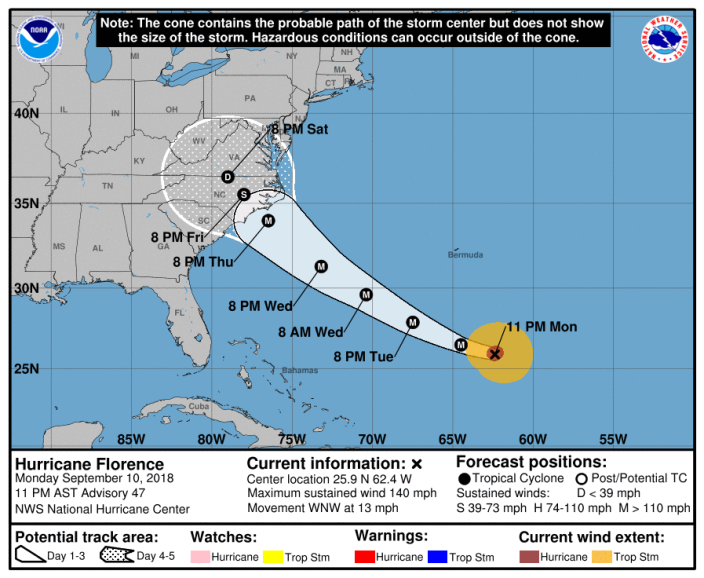

To help us better understand these products, let’s look at how they could have been used in practice during a past landfalling hurricane. Hurricane Florence made landfall along the North Carolina coast on Friday, September 14th of 2018 and presented numerous forecast challenges, as many landfalling tropical cyclones typically do. One benefit of using MOMs and MEOWs to plan, especially at longer lead-times, is that they provide stability in a situation where the forecast of the storm itself can often change quickly from advisory to advisory. Let’s take a look at what Florence’s forecast looked like about 5 days out from an expected landfall. Figure 3 is taken from the official forecast from the National Hurricane Center on September 8th at 11 pm AST.

Figure 3. NHC five-day forecast track and cone of uncertainty issued for Tropical Storm Florence at 11 PM AST September 8, 2018 (Advisory 39).

Figure 3. NHC five-day forecast track and cone of uncertainty issued for Tropical Storm Florence at 11 PM AST September 8, 2018 (Advisory 39).

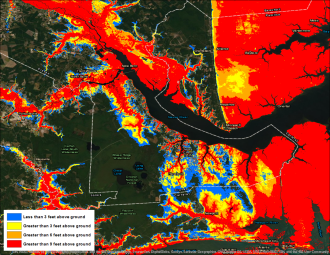

At this point, the information we know is that a potential major hurricane is roughly 5 days away from impacting some portion of the Mid-Atlantic or southeast coast. This is a good point to begin looking at the MOMs. Florence at this point is forecast to be a category 4 hurricane at landfall, so a good rule-of-thumb to follow is to look at a MOM one category higher than the forecast intensity. Let’s take a look at the Category 5 MOM to get an idea of a worst-case storm surge scenario for a portion of the North Carolina coast. You can find that image below in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Category 5 storm surge Maximum of Maximums (MOM) for portions of eastern North Carolina.

Figure 4. Category 5 storm surge Maximum of Maximums (MOM) for portions of eastern North Carolina.

Given how strong Florence could be, it’s no surprise to see potential inundation that would be catastrophic. Remember what we are looking at here and also that this is still a planning tool. This graphic is showing you the worst-case scenario from a Category 5 hurricane. That is to say that these are the highest possible inundations at each individual location for any given storm attribute. We actually shouldn’t expect to see these types of inundation values across the entire area, but given the uncertainties in the storm, all locations in this area should be prepared for these types of inundation values. It would also be prudent to consider looking at other MOMs as well, for context. For example, viewing the Category 3 and 4 MOMs gives context if Florence was to reach the coast at a lower intensity.

Good. Now let’s fast forward by 2 days. We are now 3 days out from a potential landfall. Forecast confidence has increased, but the fine-scale details are still quite blurry regarding the exact location of landfall and how strong Florence will be. But this is when you can begin to turn to the MEOWs. From this point, we can begin to whittle down the MOMs to generate a more realistic potential scenario based on the information currently available. Below in Figure 5 is the forecast from September 10th at 11 pm AST.

Figure 5. NHC five-day forecast track and cone of uncertainty issued for Hurricane Florence at 11 PM AST September 10, 2018 (Advisory 47).

Figure 5. NHC five-day forecast track and cone of uncertainty issued for Hurricane Florence at 11 PM AST September 10, 2018 (Advisory 47).

As you can see, there are some updates to the forecast track. The official forecast now calls for Florence to slow down significantly as it approaches the North Carolina coast. Let’s now talk about which MEOWs we should be looking at and explore how we select them. This is an important junction in the forecast because right now we need to evaluate what we do know, what we don’t know, and what we can and cannot rule out. Remember that MEOWs are generated individually for a particular storm category, forward speed, trajectory, and initial tide level. At this point, is there anything that we can rule out in terms of unrealistic directions that Florence could potentially make landfall? It’s ok to acknowledge that there remains some subjectivity here, but it needs to be an informed decision with an understanding that our risk tolerance is low. That being said, let’s go ahead and rule out some storm directions. Since the forecast track in advisory 47 reflects a northwestward trajectory at landfall, we’ll select that direction, as well as the two surrounding it (west-northwest and north-northwest) to account for uncertainty. How about the intensity? The latest forecast still shows Florence reaching the coast as a category 4 hurricane, so we still need to account for the possibility that it makes landfall one category stronger (category 5). Lastly, let’s consider the speed at which Florence is moving and will be moving near its landfall. The tropical cyclone forecast discussion from advisory 47 explicitly mentions that Florence is expected to decrease in forward speed as it approaches the coast:

“After that time [48 hours], a marked decrease in forward speed is likely as another ridge builds over the Great Lakes to the north of Florence.”

This is reflected in the official forecast which slows Florence down to less than 10 mph near the coast. While this certainly complicates the forecast, the beauty of using MEOWs is that it allows you to compensate for this forecast uncertainty. In this case, it’s fair that we could eliminate the MEOW forward speeds of 15, 25 and 35 mph, given forecaster confidence in Florence’s slow down. This leaves us with a forward speed of 5 mph (only a certain set of speeds is actually available to select).

Let’s quickly recap the parameters that we’ve settled on to generate our MEOW:

Intensity: Category 5

Direction/trajectory: Storms that are moving West-Northwest, Northwest, or North-Northwest

Forward Speed: 5 mph

Tide-level: High (this will always be the assumption)

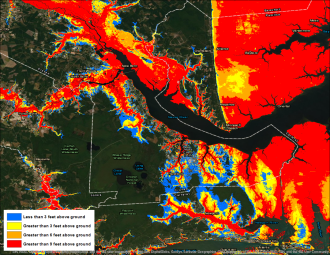

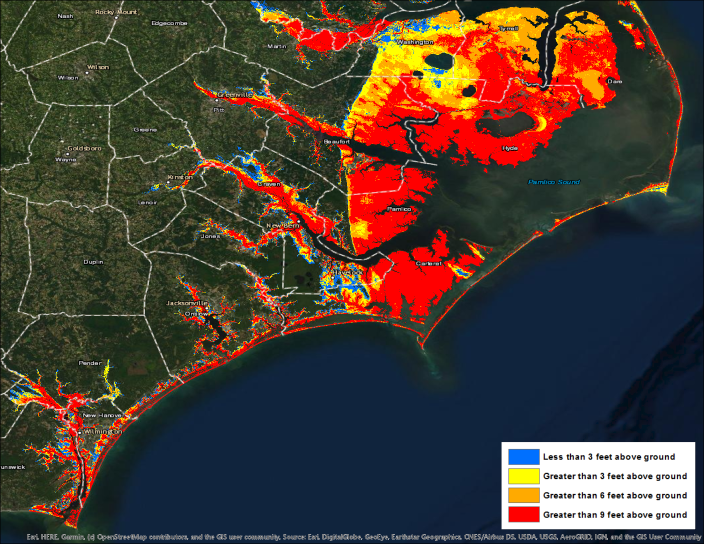

Using those parameters, Figure 6 shows the potential storm surge inundation that could occur across eastern North Carolina:

Figure 6. Composite storm surge Maximum Envelope of Water (MEOW) over portions of eastern North Carolina for a category 5 hurricane moving west-northwest, northwest, or north-northwest at 5 mph at high tide.

Figure 6. Composite storm surge Maximum Envelope of Water (MEOW) over portions of eastern North Carolina for a category 5 hurricane moving west-northwest, northwest, or north-northwest at 5 mph at high tide.

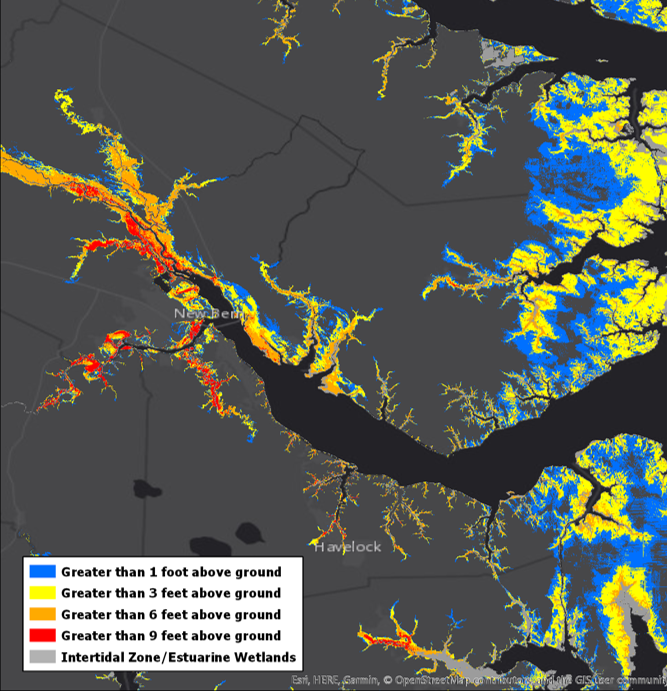

To take this one step further, let’s zoom in around the New Bern, North Carolina, area and do a quick comparison of the category 5 MOM that we initially used 5 days out and compare it to the composite of MEOWs (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Comparison of MOM (left) and composite MEOW (right) from Figures 4 and 6 above, zoomed in on the New Bern, North Carolina, area.

Remember that at this point in the forecast process, we are looking at synthetic or simulated storms to get an idea of what the near-worst case storm surge inundation could be within an environment characterized by forecast uncertainty that’s very high. What differences do you notice when you compare the two pictures above? Don’t worry–you’re eyes aren’t deceiving you. You probably don’t notice much difference at all. That’s because, unfortunately, slow-moving storms moving in a generally northwestward direction are likely some of the worst types of storms for the New Bern area. Essentially, they’re the storms that are most likely to be causing the storm surge heights you see in the MOM. Our confidence in the hurricane’s forecast has increased since we’re 2 days closer to landfall, but the storm surge risk really hasn’t gone down at all. While that might be a sobering thought, this process allows emergency managers to be as efficient as possible, appropriately assess their risk, and focus on the most at-risk areas. This is a powerful and informative process when used properly!

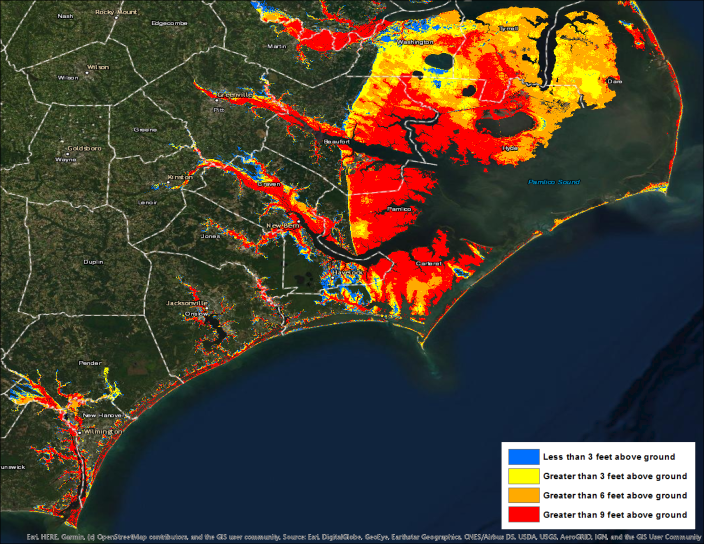

In the end, while all of eastern North Carolina did not experience the type of storm surge flooding shown in Figure 6 above (which we didn’t expect anyway), some areas did. Areas around New Bern, for instance, had as much as 9 feet of storm surge inundation above ground level (red areas in Figure 8 below). Even though Florence’s peak winds decreased while the storm moved closer to the coast, the MOM and MEOW risk maps accounted for Florence’s increasing size and slow movement (which both contribute to more storm surge) and appropriately prepared emergency managers in the area for a severe storm surge event days before Florence even reached the coast.

Figure 8. Post-storm model simulation of storm surge inundation caused by Hurricane Florence around the New Bern/Neuse River area of North Carolina.

It’s important to note at this point that MOMs and MEOWs are predominantly used during the period before storm surge or wind-related watches and warnings are in effect for the coast (more than 48 hours before wind or surge is expected to begin). Once we get to within 48 hours when watches or warnings go into effect, another suite of storm surge products–specifically the Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map and the Storm Surge Watch/Warning graphics–become available. These products refine the storm surge risk profile even further because they are based on the characteristics of the actual storm, not on the simulated storms used in MOMs and MEOWs. We plan to create another blog post addressing these products in the near future.

To really bring this home, let’s circle all the way back around to the initial discussion of risk. How does risk tolerance and risk perception affect how these products are used? We know that these products are used by a wide range of people and organizations, all of which have varying tolerances of risk. It is unrealistic to assume that we at the National Hurricane Center could know how these tolerances change across our entire user base. That being said, it is our job to gently guide the decision-making in accordance with our own risk tolerance. Said another way, we work with emergency managers and the Hurricane Liaison Team (HLT) to hopefully bring those risk perceptions more in line with the ACTUAL risk for a given storm. Emergency managers have the resources at their disposal to view MOMs and MEOWs to build out their assessment of risk tailored to their local areas. They possess the intricate knowledge specific to their area which makes them invaluable partners to us at the NHC. During a storm, we sometimes provide advice on types of MOMs and MEOWs to consult to ensure that our partners fully capture a reasonable envelope of risk. These decisions can be stressful, especially when they have to be made in line with a risk tolerance that needs to be low by necessity. Remember what the cost is again here: human lives. It’s imperative that we capture the full breadth of the risk during every storm because the cost of not doing so is immense. We are comfortable accepting that our low risk tolerance can result in some areas not experiencing the potential storm surge that was conveyed prior to a hurricane making landfall. That is, by definition, what having a low tolerance for risk means, but it’s also by design. To us, one life lost is one life too many.

— Taylor Trogdon and Robbie Berg

Reference:

Rappaport, E.N., 2014: Fatalities in the United States from Atlantic Tropical Cyclones: New Data and Interpretation. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 95, 341–346, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00074.1

Determine Your Risk

“It’ll Never Happen to Me”: Getting Past Barriers to Determining Your Hurricane Risk

Dr. Rick Knabb

Former Director, National Hurricane Center

@NWSNHC

“I’ve lived here for decades, and we’ve never had a hurricane. I figure I’m good.”

“We got hit last year, so this year it’ll be someone else’s turn.”

“I don’t want to evacuate and do all of those other things unless I know for sure it’s going to hit here.”

“I’m staying for a cat 1 or 2, and maybe a 3, but a 4 or 5? I’m outta here!”

“I just hope we don’t get hit this year.”

“It’ll never happen to me.”

These are actual statements people have made to me during my travels around the country over the years. Many of you have probably heard similar things. These are the “before” statements. What do people often say after they’ve actually been hit hard by a hurricane or other weather disaster? You know how it goes…

“In all the years I’ve lived here, I’ve never seen it like this.”

“No one told me it could be this bad.”

And this one really hurts to hear:

“I don’t have enough insurance. I’ve lost nearly everything.”

So many of us seem to be willing to take the gamble, do little or nothing, and hope that a hurricane doesn’t affect us where we live – even though we generally understand that we could lose a lot if a hurricane does come our way. Simply hoping that a hurricane doesn’t strike this year puts us in a weak position, even though we all want our families, homes, businesses and communities to be strong.

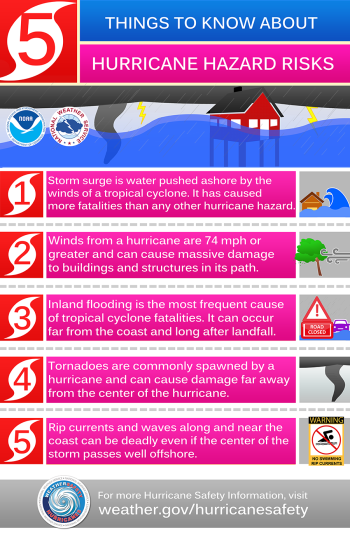

The first step for all of us to get past these initial mental barriers is to fully realize all of the hurricane risks we face. Your specific risks depend a lot on exactly where you live, but let’s get a few basics out of the way. Hurricanes are not just coastal events. Damaging and deadly winds, tornadoes, and rain-induced flooding can occur hundreds of miles from the coast and days after landfall. Even storm surges that affect coastal regions can go a lot farther inland – several miles in many locations – than many people realize. Too many unwary swimmers, surfers, and boaters have lost their lives from rip currents and waves near the coast from tropical cyclones that remain well offshore. In the United States over the past half century, nearly 90% of the direct deaths – those attributable to the forces of the storms –have been caused by water, with storm surge taking about half of these lives. Although winds can certainly be damaging and deadly, we must not underestimate how heavy, powerful, damaging, and deadly water can be when determining our hurricane risk.

The first step for all of us to get past these initial mental barriers is to fully realize all of the hurricane risks we face. Your specific risks depend a lot on exactly where you live, but let’s get a few basics out of the way. Hurricanes are not just coastal events. Damaging and deadly winds, tornadoes, and rain-induced flooding can occur hundreds of miles from the coast and days after landfall. Even storm surges that affect coastal regions can go a lot farther inland – several miles in many locations – than many people realize. Too many unwary swimmers, surfers, and boaters have lost their lives from rip currents and waves near the coast from tropical cyclones that remain well offshore. In the United States over the past half century, nearly 90% of the direct deaths – those attributable to the forces of the storms –have been caused by water, with storm surge taking about half of these lives. Although winds can certainly be damaging and deadly, we must not underestimate how heavy, powerful, damaging, and deadly water can be when determining our hurricane risk.

Some topics get a lot of attention but can actually distract us from properly assessing our hurricane risk, and from taking the right steps to confront it. We hear a lot about what the various seasonal hurricane forecasts say, what El Nino is doing, or how long it’s been since the last hurricane hit our town, or our state, or our country. But none of these things tell you anything helpful about whether you’re going to get up close and personal with a hurricane this year. No one can tell you that months in advance; the five-day forecasts are challenging enough (remember Erika and Joaquin from just last year?). We make it a point to remind folks how little relationship there is between local impacts and seasonal activity; 1992 is the classic example, a “quiet” season with only one major hurricane. Yet that one was Andrew, which struck South Florida at category five intensity. The bottom line is that it only takes one hurricane or tropical storm to make it a bad year for you, and we need to prepare the same way every year for hurricane season, regardless of whatever expectations might be floating about for the season overall.

That’s the logical way to look at preparedness, but it can be even more motivating to consider the emotional aspects of getting ready for a hurricane. How my family and I contend with our risk from hurricanes (or other perils) is a very personal and emotional topic, and I suspect that if you think about it for any length of time, it would be for you as well. The emotional response from envisioning my family and home experiencing a hurricane is a great incentive for me to take steps now to get us ready in advance – long before an actual hurricane is on our doorstep.

I don’t just think about going through the storm itself – I also plan for the potentially nasty, dangerous, and lengthy aftermath. How would I feel if, for example, my home was severely damaged by wind, water, or both – and I didn’t have enough insurance to rebuild the home and replace its contents? How much longer would it take for our lives together to get back to “normal”? What would it do to our family’s financial future to try to recover without enough insurance? This is why we are visiting our insurance agent this month for an annual checkup. Whether you rent or own, live coastal or inland, visit your insurance agent and ask lots of questions to make sure you’re adequately covered. Don’t forget flood insurance, which must be obtained separately because it is not included in standard insurance policies. Along with promising yourself to never drive your car on a water-covered road (Turn Around Don’t Drown!), getting flood insurance is one of the best ways to deal in advance with your risk of inland flooding. Inland flood risk varies by location, but a good starting point is to know that for nearly all of us, if it can rain where you live it can flood where you live. Those who live close enough to the coast to be vulnerable to storm surge have that additional reason to get flood insurance. Update your insurance now, because waiting periods make it difficult or impossible to put new coverage in place when a hurricane is actually out there and you suddenly feel the urge to visit your agent.

The reason I go shopping for disaster supplies before every hurricane season is because the alternatives are extremely unpleasant at best and dangerous or catastrophic at worst. How would I feel if a hurricane was approaching and I decided to go shopping for those supplies at the very same time it dawned on everyone else who hadn’t stocked up in advance? I’d wait in horribly long lines for things my family desperately needs, but in many cases I’d find that stores were out of those items by the time I got there. The possibility of being isolated from emergency responders for days after the storm, with power out, stores closed, and no supplies is pretty frightening. I’ll be posting another blog entry later this week about what’s in my disaster supply kit.

My neighbors might think I’m strange, but they’ll soon see me testing my window shutters to make sure I can properly put them in place. It’s been a while since we’ve had to put them up for a real hurricane threat. But far better to make sure all is in order now, than risk having to tell my wife when a hurricane warning goes up that I can’t protect our home from the debris that might soon be flying around our neighborhood in hurricane-force winds.

There are so many ways that each one of us might identify things – some of them relatively simple and inexpensive – that we can do to make our home stronger before the next hurricane strikes. In addition, when you talk to your insurance agent, ask about what discounts you could get on your premium for making some improvements to your home that might not be as expensive as you expected and that might pay for themselves over time.

Those are just some of the actions I’m taking before hurricane season starts, and these are good topics for a national conversation. Today is the first day of National Hurricane Preparedness Week here in the United States, and for the first time the week coincides with the Hurricane Awareness Tour that this year visits Gulf Coast states. The week truly promises to be bigger, better, and more effective than ever before at helping us all get ready for hurricane season. This will be the second year in a row that we bring to each stop two different types of aircraft that are critical components of our hurricane monitoring and forecasting arsenal – a U. S. Air Force WC-130J from Keesler AFB in Biloxi, Mississippi, and the NOAA G-IV jet stationed at MacDill AFB in Tampa, Florida. In addition, several organizations that have already indicated their partnership with NOAA and the National Weather Service by becoming Weather-Ready Nation Ambassadors will now spring into action in the tour stop cities or in many other locations to promote hurricane preparedness and resilience.

We hope that this tour and other preparedness week activities leave you with a greater confidence in your government at all levels, knowing that federal, state, and local officials are devoting extensive resources to plan together in advance for the next hurricane. On display this week are some of the most advanced technologies and communications tools available to help us issue the most effective hurricane forecasts and warnings, in support of evacuation and other decisions by emergency managers and to promote communication of a consistent message by our media partners.

This post is the first in a series of daily Inside the Eye blog entries that will focus on a chosen theme of the day. Some of the articles have been written by prominent experts from the emergency management community and from our nonprofit partners, and we thank them for their contributions. Later this week we will focus individual days and blog posts more thoroughly on the topics of getting an insurance check-up, stocking up on disaster supplies, and strengthening your home. We will also close out the week by talking about identifying trusted sources of information and then putting it all together in a written hurricane plan for yourself, your family, and, if applicable, your business.

We will first focus tomorrow on planning for evacuation, which is how we can most easily determine and respond to our risk of storm surge. That’s the place to start if you’re feeling overwhelmed by everything involved in hurricane preparedness. The topics of insurance, supplies, and stronger homes have a lot to do with not only safety but also recovering more quickly and fully after the storm. But it’s hard to be resilient if you’re dead, and evacuations are called beforehand by emergency managers to save lives in large numbers, primarily from storm surge that has historically caused more fatalities than any other hurricane hazard. FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate is the author of our guest blog post on this topic, so I invite you back into this space tomorrow to hear it straight from the top of the emergency management community.

I’ll just hit the high points for the moment about evacuation planning. Find out today if you live in a hurricane evacuation zone, by contacting your local emergency management agency. Don’t assume that this is only a problem for people with beachfront property. In many coastal states, the risk of storm surge extends several miles inland in some locations. If you do live in one of these zones, decide today where you’d go and how you’d get there in a real hurricane event if told to evacuate by local emergency managers. Then, when that hurricane actually threatens and those officials instruct you to evacuate, you go! And here is my plea if you live far enough inland that you find out you don’t live in a hurricane evacuation zone: identify today someone you care about that does live in an evacuation zone, and you work it out to be their inland evacuation destination. Those of you who live in a mobile home (or any other structure that is not safe from strong winds) should not plan to host evacuees, as there is a very good chance that emergency managers will also tell you to evacuate to safer shelter.

So let’s go! Let’s go dedicate ourselves to being #HurricaneStrong as our friends from the nonprofit Federal Alliance for Safe Homes (FLASH) are encouraging us to do. You’ll see and hear a lot about that initiative this week, as it focuses on the same themes we’re talking about during National Hurricane Preparedness Week. It’s about realizing that we help decide our own outcome from the next hurricane, and then helping one another to flex our collective muscles and take action now, well in advance. We can’t just let that hurricane decide what happens to us while we sit on the sidelines. Our businesses, homes, families, and friends are worth the effort, and we simply owe it to ourselves. It’s just as personal for you as it is for me.

So let’s go! Let’s go dedicate ourselves to being #HurricaneStrong as our friends from the nonprofit Federal Alliance for Safe Homes (FLASH) are encouraging us to do. You’ll see and hear a lot about that initiative this week, as it focuses on the same themes we’re talking about during National Hurricane Preparedness Week. It’s about realizing that we help decide our own outcome from the next hurricane, and then helping one another to flex our collective muscles and take action now, well in advance. We can’t just let that hurricane decide what happens to us while we sit on the sidelines. Our businesses, homes, families, and friends are worth the effort, and we simply owe it to ourselves. It’s just as personal for you as it is for me.